VCM is a gas with a molecular weight of 62.5 and boiling point of -13.9°C, and hence has a high vapour pressure at ambient temperature. It is therefore manufactured under strict quality and safety control.There are two ways to manufacture VCM from ethylene (obtained from thermal cracking); the direct chlorination method and oxychlorination method.

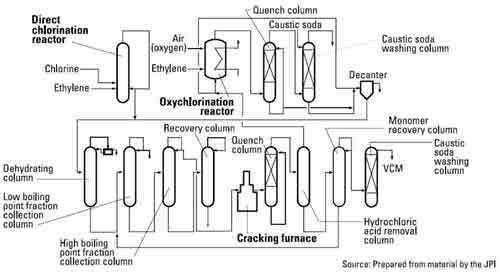

Under the direct chlorination method, ethylene and chlorine (obtained from electrolysis of salt) react within a catalyst-containing reactor to form the intermediate material EDC. EDC is then thermally cracked to yield VCM at a few hundred °C.

When the hydrogen chloride obtained as by-product from the above method reacts with ethylene in the presence of catalyst and air (or oxygen), EDC is obtained again. This is called the oxychlorination process.

When EDC from the oxychlorination process is dehydrated and then thermally cracked (together with the EDC from the direct chlorination process), VCM is obtained. These two methods are usually combined at the major VCM plants in Western Europe.

Older VCM producing technologies

Historically, VCM was not produced from EDC but by the reaction of acetylene with HCl in the presence of a mercuric chloride catalyst. The industry has spent several decades moving away from this technology and there seem to be no environmental or economic incentives to reverse this trend. Indeed, there is a strong environmental incentive to cease the use of the mercury-based catalyst involved in the acetylene-based process.

Today, this process is largely obsolete outside China, where the availability of relatively cheap local coal makes it economically attractive to continue with this technology. These historical economic drivers are unlikely to continue longterm but there is still interest in this technology where supplies of oil are scarce or potentially scarce.

VCM hazards

Care has to be taken in handling and storing VCM. Mostly because it is a highly flammable and potentially explosive gas (like the lighter fuel butane). But also because, if breathed in quantity, it is a strong narcotic (like chloroform). In fact during the 1950’s VCM was trialled as a potential anaesthetic gas for medical applications.

However, it is also now known, from studies on workers in PVC polymerisation plants during the 1970’s that VCM can be a carcinogen, with the potential to cause a rare form of cancer (cancer of the blood vessels of the liver known as angiosarcoma), if there is significant exposure over a prolonged period.

Once industry discovered this link, major action was taken to reduce the level of exposure and all manufacturing processes involving the use of VCM today are closed and all personal exposure avoided and closely monitored. Workers are regularly tested for even the lowest levels of exposure and there have been no incidences of angiosarcoma related to exposure occurring since the PVC production process was modified.

Vinyl Chloride Monomer (VCM) is the key material from which PVC is made.

Other than its flammability potential at release, once in the open atmosphere VCM quickly dissipates posing little threat to human health in such a diluted form and quickly degenerates when exposed to normal daylight.

In the polymerisation process practically all of the VCM is processed into the inert polymer chains that make up the PVC plastic. It is possible for extremely low levels of any residual unpolymerised VCM to remain in the polymer and eventually migrate into food from PVC packaging, but only at levels, which are considered totally harmless by health authorities and which fall well within European Union regulations.

Migration of even the microscopic amounts of any residual chemicals from packaging substances into food is highly regulated. This is backed up by tests from independent toxicologists. In 1993 a five-year-long Italian study, led by Professor Cesare Maltoni, Director of Bologna's Institute of Oncology, looked at the health effects on rats given mineral water from bottles made of PVC (which contained low levels of VCM) compared with water from glass bottles.

There were no noticeable differences concerning the animals' survival, weight and health conditions during the tests and, especially, the effect on tumours.

VCM Transportation

Transporting VCM presents the same risks as transporting other flammable gases such as propane, butane (LPG) or natural gas (for which the same safety regulations apply). No fatal accident has happened in Europe over the last 40 years involving the transport of VCM. The most severe accident during that time was in 1996 in the former Eastern Germany.T

he cause of this was thought to be the condition of the rail track, not the product or the rail cars carrying it. There were no casualties and no long term effects are anticipated. The equipment used for VCM transport is specially designed to be impact and corrosion resistant and the industry is committed to improving further the safety of VCM transport, as far as is reasonably possible.

Download relevant documents here:

Guidelines for the distribution of Vinyl Chloride (890kb)